This is a photo of Aunt Ryo, my mother Kazue, Grandma Uyeno, and Aunt Suki (left to right) on the morning in 1942 when the U.S. military came to take them from their home in Visalia, California to board the train to the Poston Relocation Center.

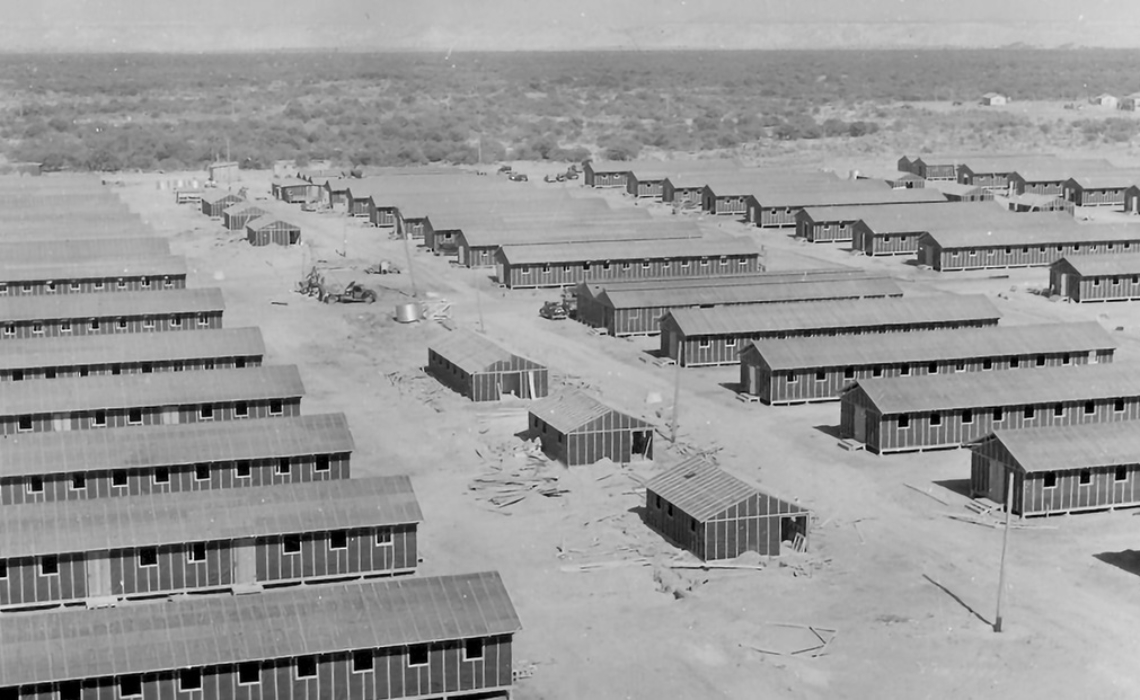

Built on the Colorado Indian Reservation in Arizona, Poston was the largest of all the relocation centers, with a population of more than 17,000 people. It had separate camps for Japanese from Northern California, the Central Valley, and Southern California. More than 120,000 Japanese Americans were interned during the war.

In this photo, which Grandpa Uyeno took, the girls are nicely dressed and smiling, as if that’s what you do when you’re about to go to a concentration camp. Aunt Ryo was the youngest daughter and was a high school student in 1942. My mother was the oldest daughter and had recently graduated from Visalia Junior College. In the photo, she’s smiling and wearing smart saddle shoes, but she’s clutching my grandmother’s arm as if to comfort her, or to comfort herself. Aunt Suki was the second oldest daughter and had just graduated from high school. I remember her always having that cheery smile. Uncle Mas, the oldest of the children, had been drafted by the Army and was in the Quartermaster Corps in Kentucky.

The train the Uyenos rode on was filled with people of Japanese ancestry from other Central Valley towns near Visalia. My mother remembered that the soldier made them keep the shades of the windows pulled down because they didn’t want anyone to know where they were going.

When the train arrived at the station in Parker, Arizona, the Japanese were put on open flat-bed trucks and driven the 25 miles to the camp in the 115 degree Arizona heat and dust.

When they got to the camp and Aunt Ryo saw where they were going to be living, she became hysterical and started crying and screaming. She wouldn’t stop, and no one knew what to do. Finally, some of the men went to the mess hall and got buckets of ice and cooled her down until she stopped crying.

I once asked my Mom how she felt on arriving at the camp. She said she didn’t remember.

When the first Japanese arrived at Poston, the camp wasn’t prepared for them. There were no beds, so the Japanese had to stuff straw into ticking to make mattresses. The women were horrified when they went into the communal bathrooms and saw the open showers and rows of toilets with no partitions.

In 1997 I went to a reunion at Poston for Japanese internees from the Central Valley and met a woman who was Aunt Suki’s best friend in the camp. She said she and Suki hated the communal bathroom and bathing in an open shower with no curtains in front of the older women. So they’d go to the shower in the afternoon. One of them would run in to see if anyone else was there, and yell, “All clear,” if the shower was vacant.

The military had also never thought about mortuary facilities, which were a necessity in a place where day-time temperatures were in the 100s. Shortly after Poston opened, an elderly man died and there was no refrigerated place to store his corpse until it could be sent on the next train to a mortuary in California.

By the time, the Uyeno family arrived at Poston, families were allowed to bring bedding with them and camp living circumstances had improved somewhat, as the Japanese had decided they had to try to make the camp into a functioning community. One of the internees was an architect and another was a civil engineer. Those two designed an auditorium and school, which the Japanese built using adobe bricks they manufactured themselves.

Many of the other internees were farmers, and they decided to start farming. The engineer designed an irrigation canal that ran from the Colorado River to the camp, which enabled Poston’s farming operations to become a large-scale community enterprise. Poston farmers grew much of the camp’s food, including vegetables, pork, and chicken.

The relocation center had a newspaper, the Poston Chronicle, and my mother was its editor. She also worked as an assistant to a Navy officer and former sociology professor, Alexander Leighton, who had been assigned to the camp to write a study about how Japanese Americans fared being imprisoned in a concentration camp. In his book, The Governing of Men, Leighton described the detrimental effects of imprisonment on family bonds. Initially, families ate together, but eventually children and teenagers ate separately in their own groups and ignored their parents.

The resentment people felt about being unjustly interned and being required to work for paltry wages led to a camp-wide general strike. Leighton also noted that people like my mother who worked with camp administrators were reviled by other Japanese and referred to as inu, the Japanese word for dog. After I read the book, I asked my mother about that, and she just said that nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans) could be mean.

The majority of Americans believed that putting Japanese Americans in concentration camps was justified. In fact, Earl Warren, who later became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, made his political career by promoting the internment of Japanese Americans as the Attorney General and then Governor of California.

The Quaker church was one of the only organizations in America that actively opposed the internment. The Quakers felt that the relocation was done, not for the stated military reasons, but for political reasons to appeal to racist groups who had been wanting to get rid of the Japanese for years. The Quakers organized a council to help sponsor Japanese college age internees get into colleges in the interior.

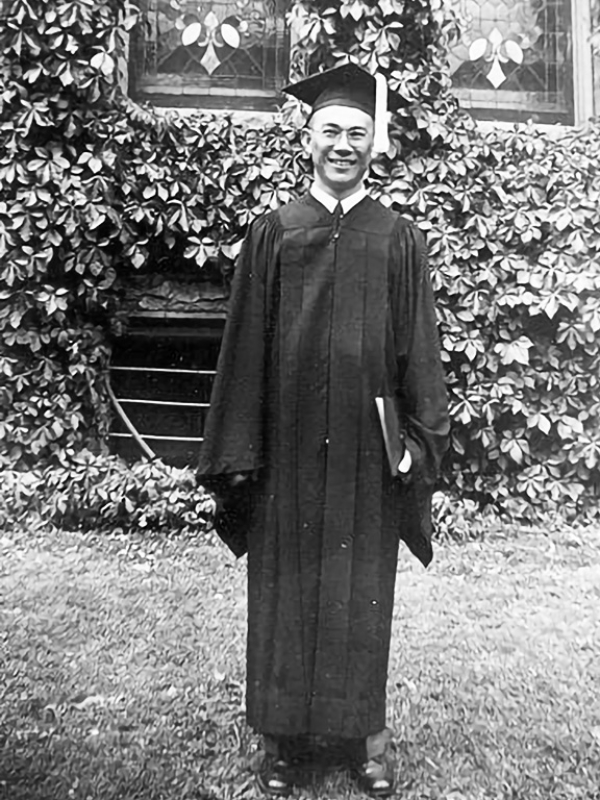

Through the work of this council, my mother was able to leave Poston to finish her college education in Chicago at the Baptist Missionary Training School, earning a bachelor’s degree in Christian Education. Aunt Suki left the camp to go to a Pfeiffer Junior College in North Carolina and then transferred to Adelphi College on Long Island to earn a bachelor’s degree in medical technology. Aunt Ryo graduated from high school in Poston and then left to attend Simmons College in Boston and Columbia University in New York City to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees in sociology.

My father, Sammie, was the youngest of the five kids of the Hasegawa family, who grew up on a farm near San Jacinto, California in Riverside County. Dad, who was a star athlete in high school, got a football scholarship to attend the University of Redlands in Redlands, California in 1940.

His college career was disrupted by Pearl Harbor. Late in December 1941, Grandpa Hasegawa was arrested by the FBI on suspicion of being a Japanese community leader, and sent to the Department of Justice prison in Santa Fe, New Mexico. In March 1942, shortly after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the relocation of Japanese on the West Coast to internment camps, Dad dropped out of of college and went back to the family farm.

The day before the ban forbidding Japanese from leaving the West Coast was imposed, my father, his sister Frances, and Grandma Hasegawa took a bus to Colorado. The three went to Brighton, in the Denver area, to stay with the Nakatas, who were family friends and relations by marriage. The Nakatas had left California years earlier and were sugar beet farmers.

In the summer of 1942, Jimmie and Tommie, the second and third Hasegawa brothers, were relocated to Poston. The oldest brother, Charles, had repatriated to Japan in 1935 and was a newspaper editor in Tokyo.

In 1943, Grandpa Hasegawa was released from the federal prison in Santa Fe, thanks to his white neighbors in San Jacinto who petitioned the government to get him out. He then went to Colorado to join the family on the Nakatas’ farm.

Because the Nakatas were having difficulty supporting so many people, my father moved to Denver, where he found a job in a dry cleaners. In Denver, he met Dr. John Foote, a Baptist missionary to Japan who had come home for vacation just before Pearl Harbor. Unable to return to Japan, Dr. Foote established the Brotherhood House in Denver, a hostel for young Japanese Americans who were trying to obtain release from the camps to move to the interior.

When Dr. Foote learned that Dad had been going to college before the war broke out, he helped my father and Aunt Frances to enroll at Ottawa University, a Baptist school in Ottawa, Kansas. My father and Aunt Frances spent the last years of the war going to college there.

In 1945 Dad graduated with a degree in economics and then took a high school teaching job in Wheaton, Kansas.

That same year, my mother graduated from the Baptist Missionary Training School and went to Poston to spend the summer with Grandma and Grandpa Uyeno, which is what all of the Uyeno children did when they had vacation or leave.

Meanwhile, the U.S. War Department had revoked the order authorizing the removal of Japanese from the West Coast, and the War Relocation Authority began closing the internment camps. The last camp was closed at the end of the year.

In September 1945, Mom left Poston to go to Denver to start a job working with girls and young women at the Denver Christian Center, a Baptist institution serving the local Japanese American community. During Christmas vacation that year, Dad went back to Denver from Wheaton to see the family and the Nakatas, and to visit Dr. Foote.

One December evening, he and other Japanese American men from the Brotherhood House went caroling at the Denver Christian Center. That’s how my father and mother met.